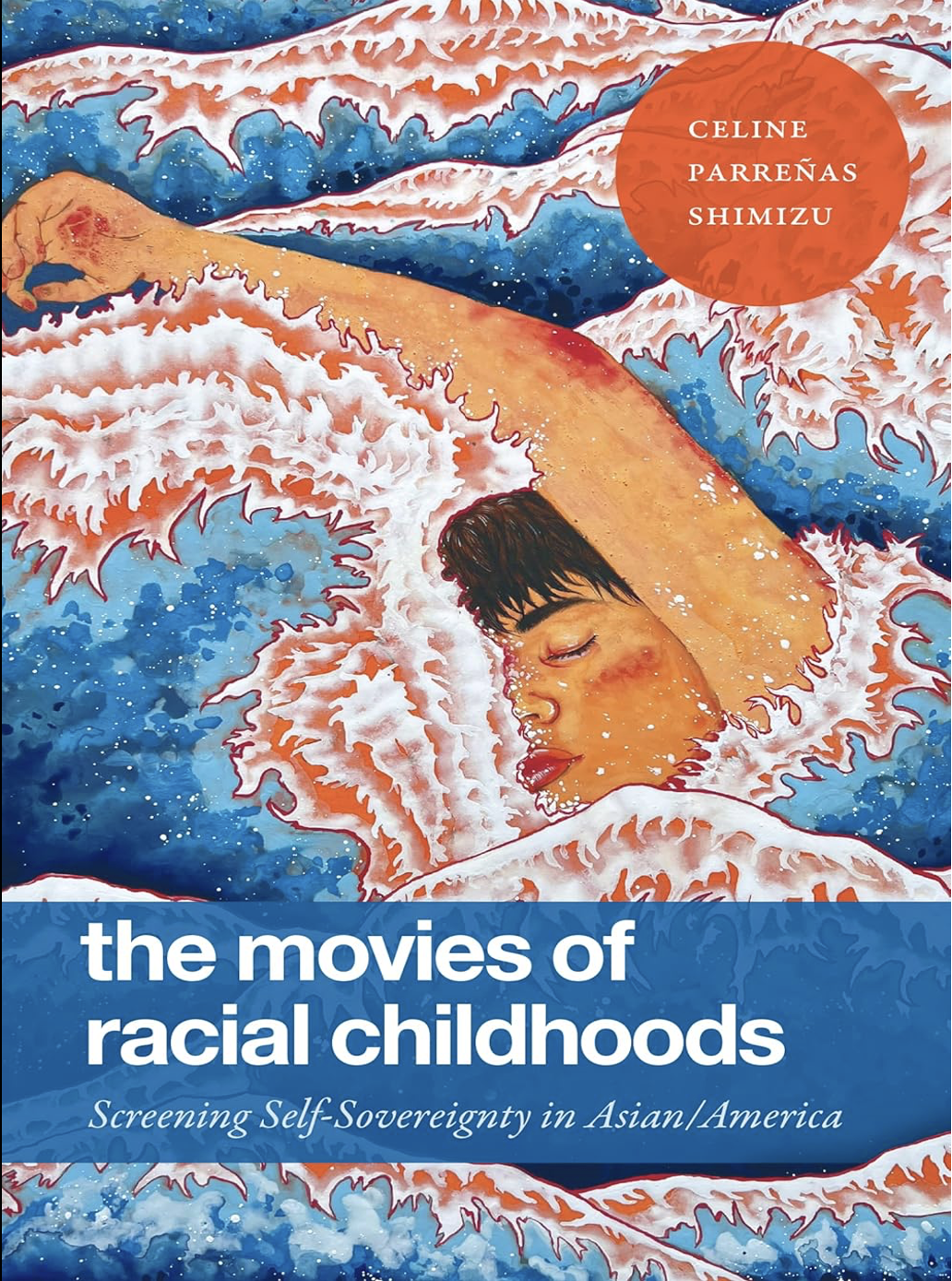

Shimizu, Celine Parreñas. The Movies of Racial Childhoods: Screening Self-Sovereignty in Asian/America. Duke University Press, 2023. $27.95.

In The Movies of Racial Childhoods, Celine Parreñas Shimizu considers the representation of Asian and Asian American children in twenty-first century film. Shimizu frames her project with a revelation: the profound impact of losing her young son spurred her to seek out depictions of Asian and Asian American children in media. This personal grief is a focal point of the study and a distinct affective lens through which she engages with themes of loss, healing, and “agentic attunement” (xi). Shimizu’s work transcends a mere academic exercise, becoming a “willing for him to live” and a way to imagine her deceased son at the ages he could not reach (ix). This deeply personal foundation, as a transnational mother who has raised Asian American children and experienced significant personal loss, lends a unique and poignant layer to her argumentation and shapes the authority of her voice.

Shimizu’s book is an original contribution to several intersecting fields, including migration studies, Asian American studies, transnational identity, literature, and film. It recalibrates existing scholarship, which primarily focuses on the transnational experiences of adults, by foregrounding the perspectives of racialized children and young people in film. Through this lens, Shimizu interrogates the complexities of migration, displacement, identity formation, and coming of age, examining cinematic representations of agency and vulnerability. She uniquely exposes how the perceived innocence of childhood is often weaponized or exploited within migratory narratives, or conversely, how children’s budding minds can become sites of cultural contestation and resilience. She also highlights how children may experience transculturation more straightforwardly than adults due to immersion in American culture through socialization and schooling.

Shimizu’s methodology is interdisciplinary, providing detailed film analysis combined with psychoanalytic approaches. She draws on the theoretical frameworks of Sigmund Freud, Heinz Kohut, Fred Pine, Teresa de Lauretis, and Jacques Lacan. She notably expands her psychoanalytic approach beyond instinct and ego theories, which she notes are typically utilized in film studies, to foreground object relations theory and self-psychology. These approaches are particularly relevant as they address the optimal conditions for child development and the role of “others” in self-formation, including animate and inanimate “selfobjects” (12). Shimizu is interested in how external factors shape the self, arguing that the self is inherently social and dependent on these selfobjects and forged through reflection and interaction with the world. This is demonstrated in her discussions of Spa Night and Driveways, which effectively show how selfobjects and fragmentation play out in the lives of queer Asian American youth, highlighting their struggles for cohesion and self-worth within challenging social contexts.

Central to Shimizu’s argument is the concept of self-sovereignty, which she defines as “the way in which children and young people must resist disciplinary control of their bodies and psyches by others if it is not for their good, as well as by the structures that organize their identities as not for themselves” (210). This involves confident independence, self-possession, autonomy, and the ability to access self-determination within specific Asian and Asian American narratives. The exploration of Yellow Rose provides a powerful illustration of healthy narcissism and self-sovereignty through Rose’s journey to claim her artistic voice and belonging despite her undocumented status. Shimizu argues that music becomes Rose’s critical selfobject, enabling her recognition and fostering a community around her, demonstrating how art can illuminate injustice and demand social change.

Another key concept is “agentic attunement,” defined as the act of attending to a child with their sovereignty in mind, both in the present moment and for their future. Shimizu explains this as a generative understanding of agency: the ability to act within constraints, and for the sake, of self and others in the face of obstacles. This concept extends to how spectators and filmmakers can interpret experiences to establish helpful narratives for child and adult development. For Shimizu, agentic attunement in filmmaking means consciously engaging with and analyzing childhood experiences to encourage agency. It also involves the “unflinching clarity” of recognizing the ongoing pain of grief and working to find purpose and meaning, even when faced with insurmountable loss (210). This is echoed in the concluding chapter, “The Power of Films about Racial Childhoods in the Time of Rampant Death,” and reflected in her analysis of Driveways, in which the quiet interactions between a young boy and an elderly neighbor model attuned care and mutual recognition.

The book also extensively employs Winnicott’s concepts of the “true and false self,” in which the true self is authentic and creative, while the false self is a facade to protect the true self from a hostile world (12). Shimizu’s examination of Andrew Cunanan in American Crime Story: The Assassination of Gianni Versace through this lens, combined with his racial and class background, provides a nuanced understanding of his pathological narcissism and self-destruction. She contrasts Cunanan’s “doomed opportunity” with the “innocent and nurtured” childhoods of his white counterparts, Gianni Versace and David Madson, exposing how racialized childhoods are often denied innocence (78).

Shimizu also uses Kohut’s idea of “healthy narcissism,” which differs from pathological narcissism, as a necessary self-love and self-regard that enables self-actualization and community building, especially for marginalized individuals who are denied recognition in society (12). This is exemplified in Yellow Rose, in which Rose’s pursuit of music and identity is framed as a journey toward healthy narcissism and self-actualization.

Finally, Shimizu incorporates Jungian psychoanalyst Thomas Singer’s concept of “cultural complexes,” which are collective ideas existing in individual psyches and collective psychic structures, influencing experiences politically, economically, socially, geographically, and religiously (194). This concept is used effectively in her analysis of The Half of It, where societal pressures (namely religion, class, and race) limit the self-sovereignty of diverse youth. Shimizu champions the film for rewriting classic narratives to center queer and Asian experiences, allowing for more fluid and contemporary understandings of sexual social identity. Likewise, her analysis of The Blossoming of Maximo Oliveros is profound in its exploration of childhood sexuality, presenting a broader “smoldering, percolating, blooming, and existing desire for bodily pleasure as well as intrapsychic connections with another” (122). This challenges conventional, often moralistic, interpretations of child sexuality in film, advocating for a focus on healthy development rather than fear. The author argues that Maxie’s “gendered femininity or blurring of gendered boundaries” is normalized in their community, offering a counter-narrative to Western taboos (119).

The strength of The Movies of Racial Childhoods lies in its innovative interweaving of scholarly analysis with deeply personal narrative. Shimizu’s vulnerability as a grieving mother who used “this book as a way to imagine how Lakas would have grown up” allows for an authentic and empathetic engagement with the cinematic representations of racialized childhoods (xvii). This approach is not self-indulgent, but rather it serves to underscore the book’s central argument: that understanding the inner lives of children, particularly those facing racialization and precarity, is crucial for fostering their self-sovereignty and for challenging harmful societal narratives.

Shimizu’s critique of the universalization of white childhood experiences is particularly vital. By centering Asian and Asian American childhoods, she challenges the assumption of “whiteness as default Americanness” in filmmaking and criticism, providing much needed diversity in discussions of film and media (26). Her work explicitly calls for greater representation and for audiences to engage with these stories with agentic attunement, recognizing the “power of representation to shape our social institutions, our interpersonal and group relations, and our intimate self-understandings” (23).

Shimizu herself acknowledges certain limitations of her research within the broader landscape of film critique. She notes the “unrelenting hunger for recognition on-screen” among Asian American moviegoers and moviemakers – a hunger that often goes unfulfilled (9). She critiques how Asian American faces have historically been deemed inscrutable, leading to misinterpretations by critics who fail to contextualize racialized images. This points to a broader systemic issue that The Movies of Racial Childhoods confronts but cannot singlehandedly solve. While her personal narrative is a strength, it also reflects the inherently speculative nature of representing childhood, as these narratives are “rendered within the limits of memory not by the people living this important age but by those who may still be affected by their origin stories and seminal memories as adults” (23). This is an issue Shimizu acknowledges and embraces, focusing on how adult filmmakers and spectators construct childhood.

The conclusion of several films, particularly American Crime Story, demonstrates that not all racialized childhoods find a “productive, or creative resolution” to trauma (79). While Shimizu seeks hope and transformation, she does not shy away from narratives in which characters succumb to destructive paths due to unresolved trauma and societal forces. This nuanced portrayal prevents the book from becoming overly optimistic, grounding her arguments in the often-harsh realities depicted in the films. The Movies of Racial Childhoods is a valuable and insightful resource. It is a meticulously researched and passionately argued work that compels readers to rethink their understanding of childhood, race, sexuality, and cinematic representation. By placing the racialized child at the center of her psychoanalytic and film inquiry, Shimizu provides a fresh and urgent perspective. The book is recommended for scholars and students in Asian American studies, film and media, childhood studies, migration studies, psychoanalysis, and trauma theory. Its accessible yet rigorous approach makes it a valuable read for anyone interested in cultural criticism, the sociology of identity, and the transformative potential of art. Shimizu’s ability to “undo cinematic harm with pleasure, affirmation, and relief” through her analysis makes reading this book a thought-provoking experience (15).

Clodagh Philippa Guerin

Image credit: IJAS Online believes that the use of the image above of a book cover to illustrate a review of the book in question is excepted from copyright under fair dealing or fair use.